I recently gave an outreach talk about my research to a group of physicists interested in linguistics, and I decided to share the summary of my talk here. All the content presented here is based on a part of my PhD thesis. This talk is now also available on my YouTube channel.

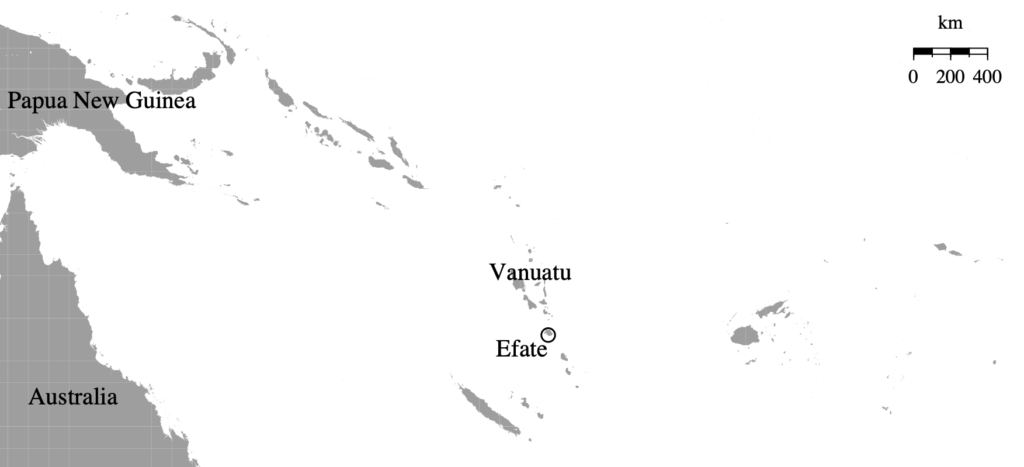

During my PhD I had the opportunity to do linguistic fieldwork in Vanuatu, on the island of Efate, see Figure 1. Vanuatu is a small South Pacific country with a population of 272,459, according to the 2016 Mini Census of Vanuatu. Vanuatu gained independence from an Anglo-French condominium in 1980 and has since moved away from its colonial past. The independence day is celebrated every year on the 30th of July and it is a great excuse to try some of the local delicacies in the Independence Park in the capital Port Vila.

The question I get a lot, especially from non-linguists, is why I chose to go to Vanuatu to do my research in linguistics. In the area of language typology it is well-known that the area of Melanesia, the region encompassing Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, and New Caledonia, features a high level of language diversity. In other words, here we attest many more languages per capita than in other parts of the world. It is estimated that Vanuatu alone has 138 indigenous languages. For linguists, this means that there is an incredible number of languages that need to be explored, since many of them have not yet been documented in sufficient detail.

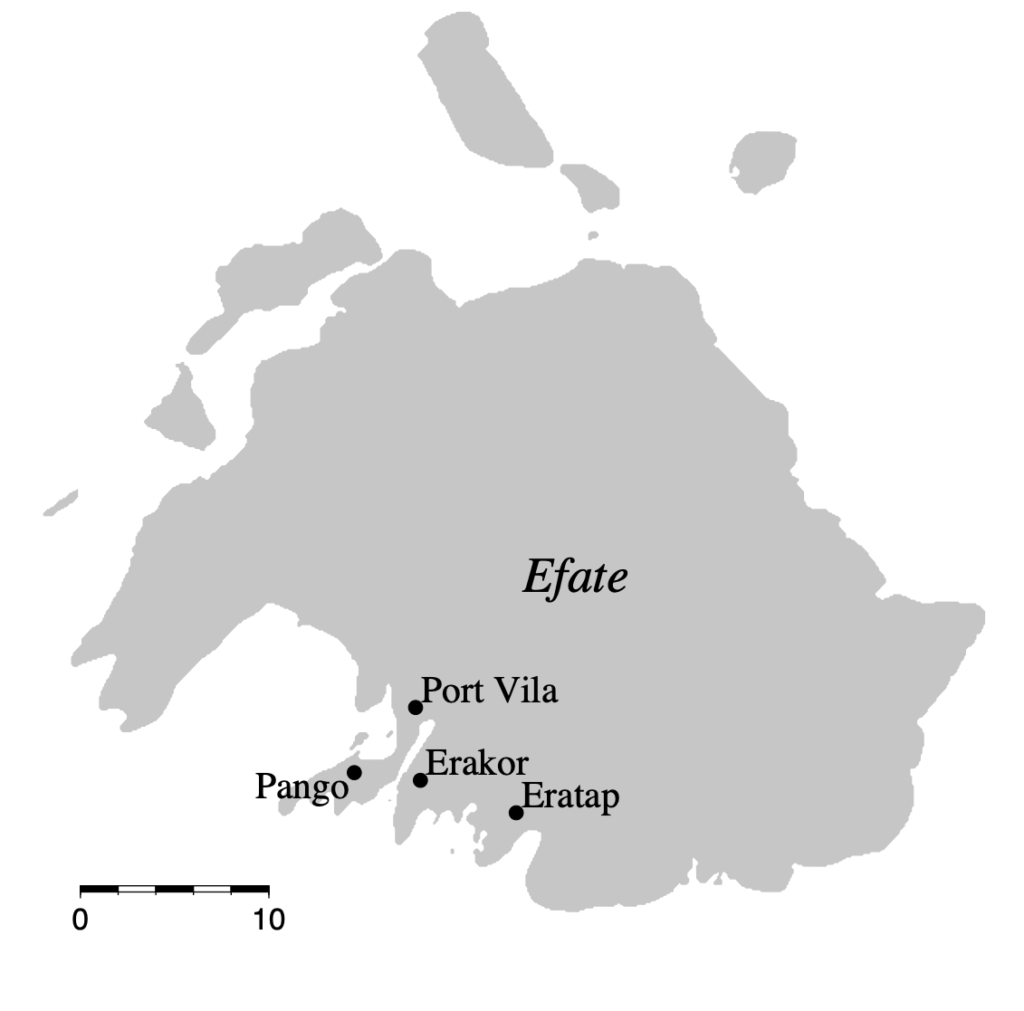

I did my fieldwork in the Erakor village, located in the vicinity of Port Vila, as can be seen in Figure 2. Just to get the idea of the scale, Efate is more or less the size of Berlin! That is why it is possible to make the ride around the island in around 2 hours.

The language I studied in Erakor is called Nafsan, which means ‘language’. Nafsan belongs to the Oceanic group of languages, which is a part of the big Austronesian family of languages. Nafsan is spoken alongside Bislama, a creole language based on English vocabulary and the national language of Vanuatu. Here is an example of what Bislama sounds like: mi save toktok Bislama, lanwis blong Vanuatu (‘I can speak Bislama, the language of Vanuatu’). At the same time, most speakers of Nafsan also learn either English or French in school and are often quite fluent.

The purpose of my field trip was to collect language data that could help me uncover grammatical meanings of certain words in Nafsan. I was particularly interested in the meaning of the word pe, which has been said to have a meaning similar to the English perfect (Thieberger, 2006). Since the actual properties of the English perfect, and also perfect in other languages, have been a matter of debate among linguists, I wanted to make sure we know what kind of perfect the Nafsan perfect pe is.

In order to understand this issue, let us first break down the meanings of the English perfect. There are at least four main meanings of the English present perfect that have been identified by linguists and one other main meaning of the English past and future perfect:

- Resultative (John has arrived.)

- Experiential (I have been to Paris.)

- Universal (John has been living in Paris since 2007.)

- Hot news (John has just arrived.)

- Anteriority (When you arrived, I had already written the letter./ When you arrive, I will have written the letter.)

By looking at the examples we can see that even though the perfect forms were used in all the examples, the intended meanings are quite different. The resultative meaning of the present perfect refers to a present state that is a result of some past event (Comrie, 1976:56), which is the arrival of John in our example above. The second meaning of the present perfect is experiential, which indicates that the described event happened at least once at any time in the past (Comrie, 1976:58), which is having been to Paris in our example. The universal meaning indicates that the state/event started in the past and is ongoing in the present (Comrie, 1976:60), and the hot news meaning denotes that the event occurred in the recent past. The past and the future perfect differ from the present perfect in that they prototypically have a reading of anteriority (I had already written the letter/ I will have written the letter in our examples above) in relation to another event (when you arrived/ when you arrive).

Another grammatical element we need to consider here is already, which frequently occurs together with the perfect, as in our example when you arrived, I had already written the letter. Since in English already often co-occurs with the perfect, it is worth asking what the difference is between the two. Linguists generally agree that the core meaning of already is the meaning of change of state, such as in the sentence the apple is already ripe, where the apple underwent the change of becoming ripe. Another component of the meaning of already is that this change of state happened earlier than expected, and was ultimately expected to happen.

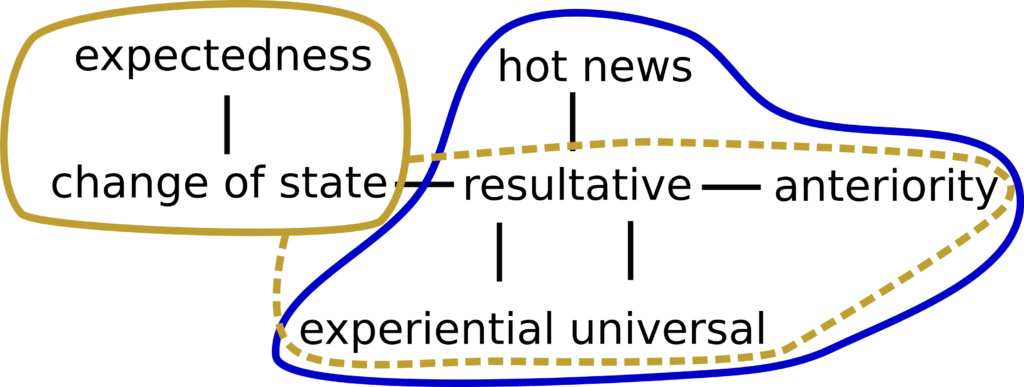

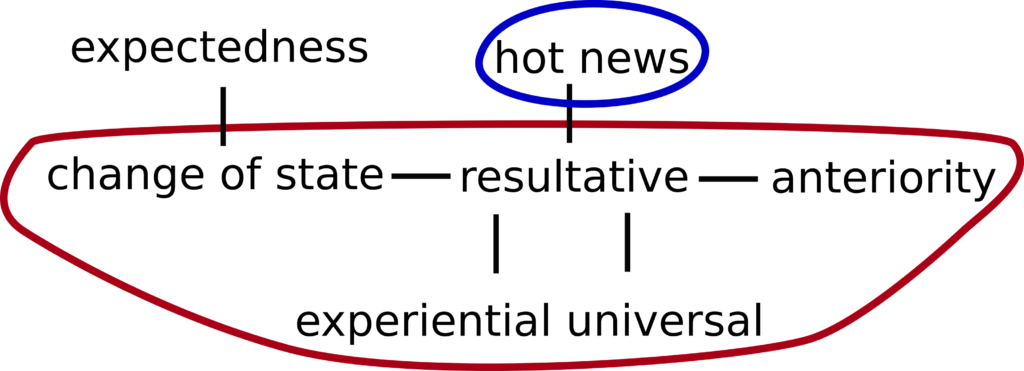

In order to visually represent these meanings and contribute to their theoretical understanding, I resorted to semantic maps used in linguistic typology. Semantic maps are geometrical representations of meanings and their relationships cross-linguistically. The meanings (nodes in the semantic map) are placed next to other closely related meanings and connected via connecting lines. Grammatical words in different languages are then predicted to occupy any area that covers adjacent meanings (see also Thanasis & Polis. 2018). Figure 3. shows such a semantic map I created with the meanings of perfect and already. The meanings of the English perfect are outlined in blue and already in yellow. The yellow dashed outline indicates that ‘already’ also combines with many perfect meanings, and in each of these combinations it maintains its core meanings of change of state and expectedness.

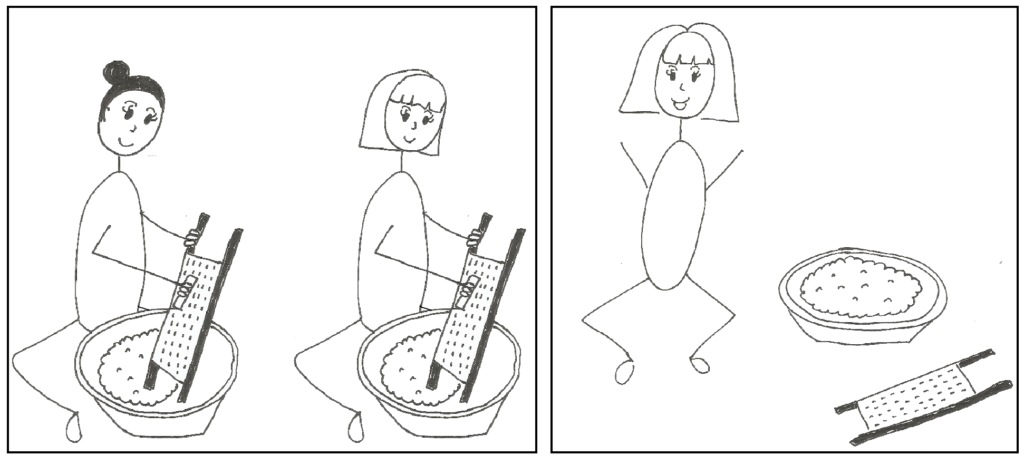

Since the aim of my research on Nafsan was to discover the meaning of the perfect pe in Nafsan, after establishing the semantic map of perfect and already in Figure 3, I needed to find out how pe relates to these meanings. In order to elicit these abstract meanings from Nafsan speakers I needed a method that would make speakers produce sentences with these meanings while remaining unaware of what I was actually looking for. For that purpose I created short storyboards (methodology developed by Burton & Matthewson, 2015), which told a story in pictures, and contained several contexts that matched the meanings from Figure 3. One example of such a context is shown in Figure 4, with two pictures from the storyboard “Making laplap“. The targeted meaning here is the resultative perfect in the second picture, I have grated the taro. As we can see, the first picture sets up an event of grating, and having grated is then a result of that event. The speakers would first hear the whole story told by me in English or Bislama and then they would retell it in their own words by looking at the pictures. This procedure aims at minimizing the influence of English and Bislama.

The storyboard method worked pretty well, and after a couple of runs with different speakers retelling the storyboards, I got my results. I was surprised to find out that the Nafsan speakers used pe for almost all the meanings of the English perfect. For instance, the targeted context in Figure 4 gave the Nafsan sentence kineu kai pe maa ntal su (literally I 1sg pe grate taro finished). The only meaning that pe is not used for is hot news, and that is because there is another word used for this meaning, and that is po. Figure 5 shows how the meanings in the perfect semantic map are divided in Nafsan. Another interesting observation is that the Nafsan perfect has an additional meaning of change of state, which we mentioned above as the core meaning of already.

In my PhD thesis I argued that these two points of departure from the English perfect bear important consequences for our understanding of grammatical meanings in general. For instance, since po already expresses the meaning of hot news, it is unlikely that Nafsan would resort to using yet another word for the same meaning. This explains why pe is not used for a meaning that at a first glance doesn’t seem too different from the resultative — po is simply more informative. Regarding the additional meaning of change of state, Nafsan doesn’t really have a word that would neatly correspond to already like in English, and this could explain why perfect needs to extend to the change-of-state meaning, which can also be regarded as a stative version of the resultative meaning (Koontz-Garboden, 2007).

An objection that could be raised to the research I described above could be why comparing Nafsan to English? What about all the other languages and their ways of expressing these meanings? It is true that the linguistic tradition has been heavily influenced by Indo-European languages, especially English, and there are quite a few things in the English grammar that are not so common in other languages. I think that the English perfect is also tacitly assumed by many linguists to be one of those English categories that unites disparate meanings together. However, a closer look at some Oceanic languages reveals that maybe the particular grouping of the meanings we saw in Figure 5 is not so uncommon. Besides Nafsan, I analyzed four additional Oceanic languages, Toqabaqita, Unua, Niuean, and Māori, and I came to an interesting realization. The perfects in these languages can express at least the experiential, resultative, and the anteriority meaning, while the Toqabaqita and the Unua perfects were equivalent to the Nafsan pe, as in Figure 5, and the Māori perfect denoted all the meanings except for expectedness. This small sample of a couple of Oceanic languages is far from proving that the perfect category with the properties described here is wide spread across the world. However, it brings important evidence at least in the regional context of Oceanic languages, which seem to exhibit surprisingly common patterns of perfect meanings, and an equally surprising similarity to the English perfect. Maybe this means we can feel hopeful that at least some of the relationships between the perfect meanings, as shown in the semantic maps above, capture certain universals of human cognition.

References

Burton, Strang & Lisa Matthewson. 2015. Targeted construction storyboards in semantic fieldwork. In M. Ryan Bochnak & Lisa Matthewson (eds.), Methodologies in semantic fieldwork, 135–156. New York: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190212339.001.0001.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Georgakopoulos, Thanasis & Stéphane Polis. 2018. The semantic map model: State of the art and future avenues for linguistic research. Language and Linguistics Compass 12(2). e12270.

Krajinović, Ana. 2018. Making laplap (MelaTAMP storyboards). Zenodo doi:https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1421185.

Koontz-Garboden, Andrew. 2007. Aspectual coercion and the typology of change of state predicates. Journal of Linguistics 43(1). 115–152.

Thieberger, Nicholas. 2006. A grammar of South Efate: An Oceanic language of Vanuatu. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.